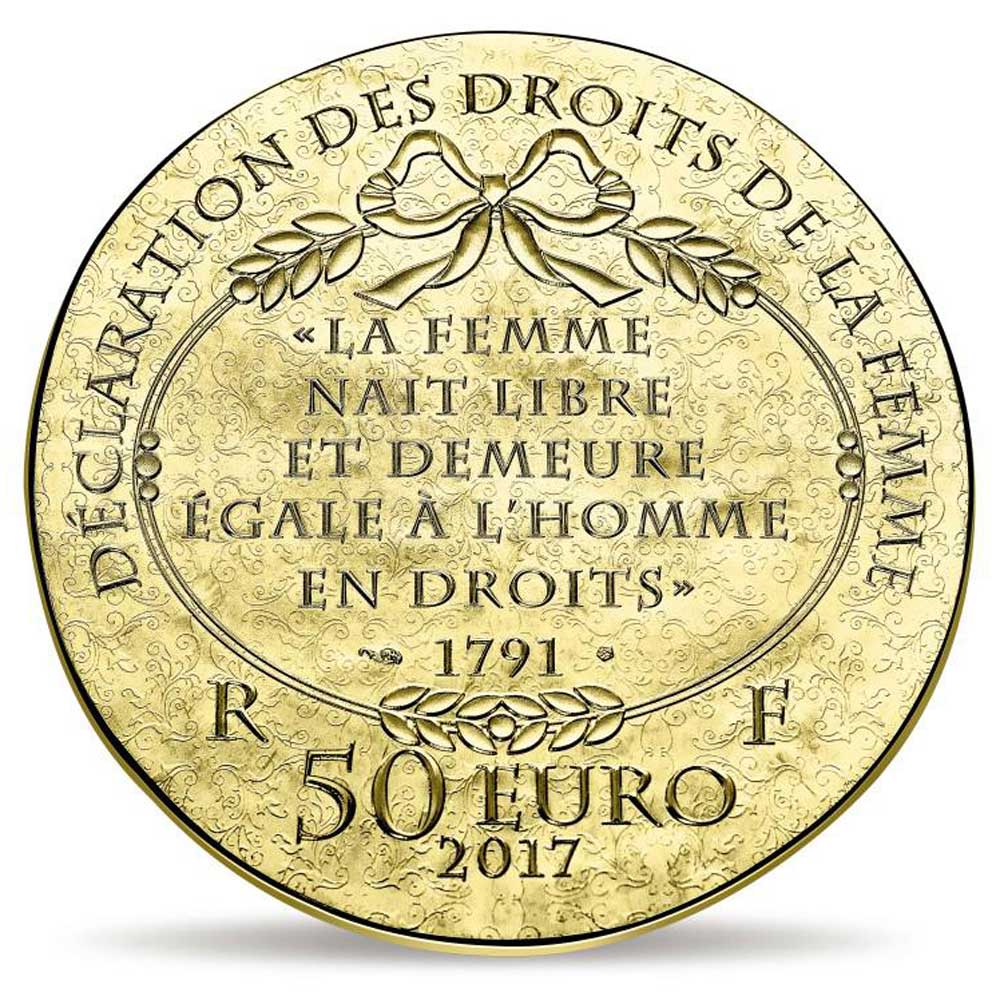

Point by point, she reformulated the original declaration, highlighting male bias in its conception of ‘the citizen’ and accusing it of ‘scorn for the rights of women.’ De Gouges understood the power of language and communication. In it she rewrote each of the 17 articles of the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen - a key text of the French Revolution. I: 1789-1791, vol.In 1791, Olympe de Gouges published her Declaration of theRights of Woman and of the Female Citizen. Écrits politiques, présentés par Olivier Blanc, vol. Gouges : une humaniste à la fin du XVIIIe siècle (Cahors, Éditions René Isabelle Brouard-Arends, ‘Olivier Blanc, Marie-Olympe de Olivier Blanc, Marie-Olympe de Gouges, 1748-1793: desĭroits de la femme à la guillotine (Tallendier, 2014) Joan Wallach Scott, Only Paradoxes to Offer: Frenchįeminists and the Rights of Man (Harvard University Press, 2021), Sherman, Reading Olympe de Gouges (Palgrave Sophie Mousset, Women's Rights and the French Revolution:Ī Biography of Olympe de Gouges (Routledge, 2017)Ĭarol L. Karen Green, A History of Women's Political Thought inĮurope, 1700-1800 (Cambridge University Press, 2014), especially theĬhapter 'Anticipating and experiencing the revolution in France'Ĭarla Hesse, The Other Enlightenment: How French Womenīecame Modern (Princeton University Press, 2001) The Birth of Democracy (Chicago University Press, 1994) Geneviève Fraisse, Reason's Muse: Sexual Difference and Brown, ‘The Self-Fashionings of Olympe de Gouges,ġ784-1789’ ( Eighteenth-Century Studies, The Johns Hopkins University Katherine Astbury at the University of Warwick Reader in 18th century French studies at King’s College LondonĬatriona Seth at the University of Oxford Professor of French Studies at the University of Warwick Marshal Foch Professor of French Literature at the University of Oxford

Two years later this playwright, novelist, activist and woman of letters did herself mount the scaffold, two weeks after Marie Antoinette, for the crime of being open to the idea of a constitutional monarchy and, for two hundred years, her reputation died with her, only to be revived with great vigour in the last 40 years. Where the latter declared ‘men are born equal’, she asserted ‘women are born equal to men,’ adding, ‘since women are allowed to mount the scaffold, they should also be allowed to stand in parliament and defend their rights’. This was Olympe de Gouges (1748-93) and she was responding to The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen from 1789, the start of the French Revolution which, by excluding women from these rights, had fallen far short of its apparent goals. Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the French playwright who, in 1791, wrote The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)